'Malcolm & Marie': A Man, a Woman and One Feature-Length Argument

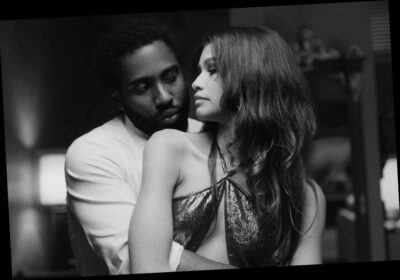

Life’s too short to make this review long. So, in the nature of Sam Levinson’s Malcolm & Marie — which, mercifully, jumps right to it — let’s dive right in. It’s a film-length argument between Malcolm (John David Washington), a filmmaker who’s just premiered a new movie, and Marie (Zendaya), his girlfriend and the woman whose own life story — one that involves self-abuse, addiction and recovery — provided key source material for said movie. We meet them post-premiere, back at home, and it’s clear this couple isn’t on the same page. Malcolm is ebullient. Marie … isn’t.

We soon found out why. Despite being his main squeeze and having seen the guy through the making of this movie (which, as anyone who’s dated an insecure artist knows, is a full-time job) — and despite this being a movie that not only borrows from her life but specifically from the darkest, lowest recesses of that life — Malcolm forgot to thank Marie in his speech at the premiere. A glaring oversight, to be sure, and one apparently inspired by an actual mistake that Levinson made and may still feel some guilt over. Which may help explain why Malcolm & Marie‘s streamlined, overly blunt approach to its characters’ psychologies feels so obvious and declarative.. Netflix allegedly spent $30 million to acquire the streaming rights, and the entire cast and crew may have (understandably) wanted above all else to get back to work and keep creating during the pandemic. But the movie still feels tailored to an audience of one.

Which isn’t to say that the punches thrown don’t have weight and occasional power. The underlying theme here is of a director — we’re talking about Malcolm now — who only nominally knows how much he needs his partner. Look at the way he cuts her down: “You weren’t the first.” Meaning: You think you inspired this bit from the movie, or this one, or that one, and this film is bigger than you, and these things aren’t all about you. (Ouch.) He tries to pin this back on her, as a consequence of her addiction, as if she’s addicted to the very idea of being an addict. “That’s what makes you so fucking unique, right? That’s what makes your contribution so much more significant, right? Get the entire fuck out of here. You’re not the first broken girl I’ve known, fucked, or dated.”

So: he’s an asshole. She hangs around for the sake of being eviscerated (he says); he keeps her hanging around for good material (she says). The movie seems to want to come off equally interested in both characters’ flaws, but in that regard, Malcolm is fighting with his hands tied behind his back. Marie’s hurt is real; her inciting complaint is legitimate. And Washington is such a loose cannon in the role that Malcolm’s sense of Marie’s failures prove a bit less convincing. There’s no probing here. Just yapping.

There are a few funny moments: Malcolm whining about the Los Angeles Times paywall. Malcolm drunkenly taking out his consternated excitement on a bowl of macaroni. Malcolm huffing and puffing over a few small criticisms in a “dumbass, pussy-ass, bitch-ass … cocksucking, motherfucking, dog-dick” review that, as Marie coolly reminds him, also called his movie a masterwork. Claims that Malcolm & Marie lacks self-awareness don’t quite hit; Levinson knows what he’s doing when he lets Malcolm drone on and on, howling at the moon, huffing and puffing as he stomps back and forth while Marie looks on with a wry smile that says, “This guy …”. (In a role that otherwise feels better-suited to a more jaded, less emotionally open star, this scene — these reactions — are where Zendaya shines.)

Meanwhile, the racial hang-ups Malcolm wears on his sleeves — the way he rails at woke, overeducated critics as if he, too, isn’t privileged and overeducated — are again not something the film is unaware of. (Whether it’s aware of the awkwardness of a white director transposing his own battles with critics onto this black character, and the further awkwardness of tying those battles up into a neat racial complaint, is another matter, and one that Malcolm no doubt has feelings about, I’m sure.) This is the stuff Marie sees in the man that he apparently doesn’t see in himself, a stack of cards she can hold close until the time comes to nick the jugular, mid-fight, with a glint of insight into Malcolm’s flaws.

I’m tempted to say that these are the director’s ways of demonstrating, profusely and with good actors and lots of shouting and gesticulation, the writer/director’s insights into his own flaws. Is there much more to the movie than that? Does Levinson do much with all that awareness? Not really. The black-and-white glossiness of it, the close-ups, the knock-down drag-out verbal tussles: This is the kind of movie that practically begs comparison to John Cassavetes, while also giving us a lead character who’d berate us for making the comparison. It gets a little boring. Turn the movie off at the 20-minute mark and you can ultimately still say you’ve seen the entire thing.

You’ll have missed out some accomplished lighting and camera-work, some good jazz, and a pleasing tour of a pretty incredible house. But despite the actors’ efforts, you won’t have learned much more about either of these people. Malcolm & Marie is a five-paragraph essay: the nexus, the thesis, is right there up front, and everything that follows is just supporting evidence. Maybe that’s the point. “Cinema doesn’t need to have fucking a message,” Malcolm characteristically rants. “It needs to have a heart — an electricity.” Agreed. But since Malcolm & Marie is lacking in all of the above, what’s the point, really?

Source: Read Full Article