Today will prove the soul of Britain we witnessed in 1953 endures

All utterly changed, but today will prove the soul of Britain we witnessed in 1953 endures: Last time, the country was as grey and stodgy as the food. And yet we have closer ties to that vanished age than we imagine, says historian DOMINIC SANDBROOK

- Follow MailOnline’s new Royals channel for all the latest news and updates

On the morning of Tuesday, June 2, 1953, Britain awoke to grey skies and pouring rain. For once, though, nobody cared about the weather. For this was the day to which millions of people had looked forward for months — the Coronation of Elizabeth II.

In a country still haunted by the sacrifices of World War II, with many cities scarred by bomb damage and the economy hidebound by austerity, the late Queen’s Coronation brought a welcome splash of colour and excitement.

To the spectators packed into the streets of London, the pomp and pageantry made for an unrivalled spectacle. The guests included some of the most celebrated statesmen on the planet, from the indomitable lion Sir Winston Churchill to Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of a recently independent India.

And the event itself was a heady blend of ancient and modern, the reassurance of tradition and the shock of the new.

On the one hand, the gleaming Gold State Coach, an emblem of Britain’s monarchical heritage; on the other, the roar of fighter planes hurtling overhead.

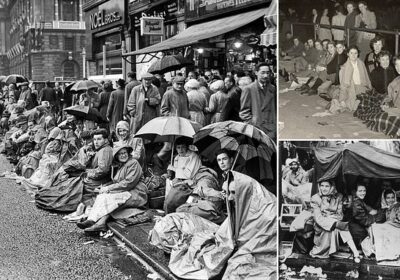

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Crowds of well wishers line the route of the Coronation procession in London on June 2, 1953

A group of people sitting on the edge of the pavement on the ‘Mall” to wait for the procession on Tuesday.They have blankets, food, and hot drinks

A crowd of people waiting on The Mall for an all-night vigil for the Coronation procession. The 1953 coronation was a morale boost in the tough post-war years as millions celebrated the historic day

Such was the mood in early 1950s Britain — a country, in many ways, astonishingly different from our own. Yet at the heart of the spectacle, then as now, was a single individual, the focus of so many ordinary people’s respect and affection.

While our King, at 74, is the oldest British monarch ever to be crowned, his late mother was just 27 for her own coronation in Westminster Abbey.

Thanks to her youth, Elizabeth was already the object of unrivalled worldwide fascination. As Churchill, her first Prime Minister, put it, ‘all the film people in the world, if they had scoured the globe, could not have found anyone so suited to the part’.

For Elizabeth, the Coronation was above all a solemn spiritual occasion. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, anointed her with oil and placed the crown on her head, this was the moment she dedicated herself, body and soul, to the service of her people.

The fact that Archbishop Fisher was a Victorian, born in 1887, is a startling reminder of our late Queen’s extraordinary longevity.

READ MORE: Coronation 101! Your ULTIMATE guide to King Charles’ historic day – from where YOU can watch all the action on-screen in the US to a minute-by-minute breakdown of all the pomp and ceremony

And in many respects the vast crowds who lined the streets of London, more than a million people defying the driving rain, look like figures from a vanished age. Study their pale faces in the newsreel footage, and you’re immediately struck by how small and thin they seem, compared with their counterparts today.

Their clothes are heavy and grey, to keep them warm in an age before central heating. And it’s notable how alike they look, products of an age of collective consensus, rather than individual self-expression.

This was a country of smog and fog; of thick greatcoats, stodgy food and heavy coins. It was the Britain of Stanley Matthews and Billy Wright, Aneurin Bevan and Anthony Eden, Vera Lynn and Arthur Askey.

Capital punishment still had strong support. Only a few months earlier, in January 1953, the 19-year-old burglar Derek Bentley had been hanged for the murder of a policeman, despite the fact it had been his 16-year-old friend who fired the fatal shot.

More than one in four people had outside toilets. Fridges and washing machines were expensive luxuries, and there were just 3 million cars on the roads, compared with more than 35 million today.

Politically, Britain in 1953 was extraordinarily backward-looking. The Prime Minister, Churchill, had first entered the Cabinet in 1908, almost half a century earlier. He had suffered several minor strokes, and even his closest friends admitted that he was coasting on past glories.

Much of Churchill’s energy was devoted to the tasks of preserving peace in the era of the Cold War, and holding together the colonies of the crumbling British Empire.

Yet by the time of the Coronation, his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, was already negotiating the withdrawal of British troops from the Suez Canal (beginning the ignominious saga that would later blow up Eden’s premiership).

The Empire loomed large in the national consciousness that damp day in 1953, thanks not least to the troops from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Pakistan, South Africa and Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) who joined the procession. In her Coronation Day speech, the Queen pledged to uphold ‘the living strength and majesty of the Commonwealth and Empire; of societies old and new; of lands and races different in history and origins but all, by God’s Will, united in spirit and in aim’.

And even the recipe created especially for the palace banquet — curried coronation chicken, invented by the food writer Constance Spry and the chef Rosemary Hume — was a reminder of the glories of the Empire in India.

For those who wondered whether, in reality, the Empire’s days were numbered, fate offered a dramatic rebuke. On the very morning of the Coronation, the news broke that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had done the impossible and conquered Mount Everest in the name of Commonwealth and Empire.

Crowds in the rain in Trafalgar Square, London watching the troops march past on the return from Westminster Abbey after the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

To the newspapers it seemed a blessing from heaven, a sign that God was smiling on the country once again. ‘Be Proud of Britain on this Day,’ roared one headline, exulting at a ‘stroke in the true Elizabethan vein, a reminder that the old adventurous, defiant heart of the race remains unchanged’. Yet for all the idealistic talk of a New Elizabethan Age, Britain in 1953 was a tired, grey, even threadbare country, exhausted after more than a decade of austerity.

London, the backdrop for the new Queen’s big day, struck one visitor a year earlier as ‘scarred and dingy’, a vision of ‘rubble, greyness, smog, poverty, garish whores on the streets in Soho, trams still running along Kingsway, tramps sleeping on the Embankment and under the Arches’.

The writer Cyril Connolly called it ‘the largest, saddest and dirtiest of great cities, with its miles of unpainted, half-inhabited houses, its chopless chop-houses, its beerless pubs . . . under a sky permanently dull and lowering like a metal dish-cover’. That might sound harsh. Yet only a few months earlier, in December 1952, the five-day ‘Great Smog’ had killed an estimated 10,000 people, who died of respiratory diseases thanks to the unusually cold weather, windless conditions and thick fog of coalsmoke that hung over London.

The capital in 1953 wasn’t just colder and damper than today’s London, it was sootier, smokier and smellier. It’s easy to forget, for example, that the majority of men puffed on cigarettes, cigars and pipes, including, amazingly, almost nine out of ten doctors.

More than one in ten houses had no electricity, and most were heated by a coal fire in a single room. In the back streets of industrial towns and cities — as London still was in those days — smoke poured from the fireplaces of hundreds of terraced houses to mingle with the black clouds belching from factory chimneys.

Sir Winston Churchill (front), his son Randolph Churchill (back left), and his grandson Winston Churchill (right), in Coronation robe

Coughs and colds were common; dirt clung to people’s clothes. As late as 1950, one survey found that nearly half of all homes had no bathroom, with people filling tin baths by kettle instead.

In other ways, too, the Britain of 1953 seems utterly different from our own. The population was smaller, at just 51 million, and much younger, with almost 22 million people under the age of 30. People married and had children earlier.

And with mass immigration only just dawning, black and brown faces were relatively uncommon. Look at any newsreel footage of the Coronation crowds, and the people are almost entirely white.

In some ways, therefore, Britain in 1953 was much more conservative, settled and tight-knit than it is today. In its special Coronation supplement, the Observer newspaper even declared that ‘the country is today a more united and stabler society than it has been since the Industrial Revolution’.

Yet there were darker sides — not just the signs in landladies’ windows (‘No blacks, no Irish’), but the relentless persecution of people who were different. A good example is the Metropolitan Police’s crackdown on homosexual activity, which was inspired by the demand to ‘clean up the streets’ in time for the Coronation.

Only months earlier, the Sunday Pictorial (today the Sunday Mirror) had run a three-part series under the banner headline ‘Evil Men’, promising ‘an end to the conspiracy of silence’ about homosexuality in Britain. According to the paper, this ‘spreading fungus’ had infected ‘generals, admirals, fighter pilots, engine drivers and boxers’, and it demanded a ferocious prosecution drive before the Queen’s big day.

The eyes of the world’s representatives follow the Queen’s progress through Westminster Abbey as she arrived for her Coronation

In this respect, I imagine few of us would want to see the clock turned back. At its best, 1950s Britain could be supportive and united. But at its worst, it was stifling and repressive.

While it’s tempting to see Britain back then as a lost world of timeless conservatism, untouched by the seismic social and cultural transformations of the Swinging Sixties, change was already under way.

Indeed, the Coronation itself wasn’t just a link with the hallowed past. As the first significant televised occasion in British history, it was a glimpse into the small-screen future.

Though television was in its infancy, sales of new black-and-white TVs doubled in the month before the big day.

And although only about 3 million people owned a set, it’s estimated that about 25 million, more than half of the adult population, squeezed into their neighbours’ sitting rooms to watch hours of the BBC’s reverential coverage.

Thanks to the Mass Observation project, in which volunteers recorded their impressions of daily life, we know what people made of what a teenage diarist excitedly called ‘the Great Day’.

READ MORE: Kate shines as she joins party in the palace with foreign royals and world leaders ahead of Charles’ coronation tomorrow… but where was Camilla?

The Princess of Wales met the First Lady of the United States of America, Jill Biden, and the First Lady of Ukraine, Olena Zelenska on Friday

On one farm where half a dozen women gathered to watch the coverage, the general feeling was anxiety for the young Queen.

‘It’s a tiring day for her. Two-and- a-half hours in the Abbey. It’s the whole day really,’ one woman said worriedly.

‘I expect she packs herself up a couple of sandwiches,’ another said. But a third was concerned that it was all going to be a bit dull. ‘I wish some of the ladies-in-waiting would trip over,’ she said wistfully. ‘Give us a bit of fun.’

When the Coronation was over, though, everybody agreed it had been marvellous. ‘Once it started, we couldn’t tear ourselves away from the set,’ one woman wrote.

‘If anyone had said beforehand we would sit spellbound for so long, I would have thought it was impossible,’ another viewer reported. But ‘it was an experience that I will not forget as long as I live’.

Were these viewers in 1953 so different, then, from the millions who will tune in to watch the King’s Coronation? Perhaps not.

After all, many of their anxieties — technological change, international unrest, the morals of the young, even the rising prices in the shops and the threat of nuclear attack by the Kremlin — sound remarkably familiar today.

Their clothes, their habits, even their accents might strike many people as old-fashioned. But in their affection for the monarchy and their uncomplicated love of country, those viewers in 1953 surely weren’t so different from the tens of millions of us who will raise a glass to the King today.

What, wondered George Orwell a few years before the Coronation, does one generation’s Britain have in common with another’s? On the face of it, nothing.

‘But then,’ he went on, ‘what have you in common with the child of five whose photograph your mother keeps on the mantelpiece? Nothing, except that you happen to be the same person.’

Pure sentimentalism? Perhaps.

But when the crowds pour into the streets today to cheer our newly crowned King, they’ll be following in the footsteps of countless Britons in years gone by, who shared many of the same hopes, dreams and fears familiar to us all.

Celebrities, politicians, even individual kings and queens come and go. But the spirit of the nation remains, and the soul of Britain endures. And so amid the Coronation celebrations, let’s raise a glass to those who came before us — the men and women who built the foundations on which we stand.

Source: Read Full Article