The shocking story behind NYC’s Cooper Hewitt family

More On:

scandals

West Point expels eight cadets, holds back 53 others for cheating

Morgan Stanley reveals nearly $1B loss from Archegos implosion

Hunter Biden: I was so crack-addled, I forgot pants — but I was also very qualified for Burisma

Lost his Cuo-jo? NY budget shows how much gov’s scandals have drained his power

When Ann Cooper Hewitt was 3 years old, she was caught with her hand down her pants.

In the eyes of her mother and doctors back around 1920, this indicated that the girl was irreparably damaged, a “feebleminded” “idiot” with no chance of living a normal life. This began an odyssey of abuse that would later result in her being sterilized without her knowledge.

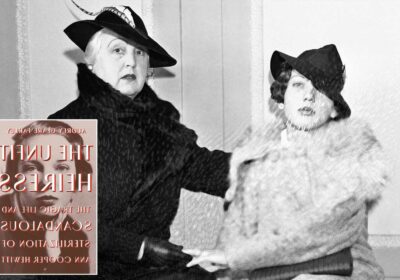

“The Unfit Heiress: The Tragic Life and Scandalous Sterilization of Ann Cooper Hewitt,” (Grand Central Publishing) by Audrey Clare Farley, tells the sad and shocking tale of Cooper Hewitt, the daughter of famed engineer and inventor Peter Cooper Hewitt, and how her case reflected a time when eugenics was not only frighteningly common, but widely accepted in the US. (Farley notes that this is a work of “creative nonfiction,” namely, while the facts are true as stated, “some scenes, dialogue, and narrative details have been constructed for dramatic purposes.”)

Ann’s mother, Maryon Cooper Hewitt, was an abusive parent. In her early 20s, Ann would show a court of law the scar on her forehead from when her mother reportedly smashed a wine glass against it, and a burn on her forearm from her mother’s cigarette.

During the court case — wherein she sued her mother for half a million dollars for having her sterilized without her knowledge — she told of being locked in her room all the time as a child and never being allowed to have friends.

“My mother never came near me,” she testified. “The maid would dress me in the morning, then leave me there for the day. I would often go to sleep in my clothes.”

Sadly for Ann, two factors gave her uncaring mother motive and means for an even harsher form of cruelty.

When Peter Cooper Hewitt — whose grandfather founded the Cooper Union, and whose father, Abram Hewitt, and uncle, Edward Cooper, were both mayors of New York — died in 1921, his estate was worth over $4 million, the equivalent of $59 million today. According to his will, Ann would receive two-thirds of this, and her mother would receive one-third.

A caveat, however, stipulated that should Ann die childless, her share would revert back to her mother.

As it happened, this coincided with a time in the US when forced sterilizations were becoming widely accepted throughout the country, including among the medical establishment.

The country’s gender attitudes were so Victorian at the time that the trend of women riding bicycles and stopping to chat with friends was seen as problematic.

“Many worried that intense conversations endangered a woman’s health,” writes Farley. “They had long been told that the gentler sex required rest and seclusion to avoid overtaxing the nervous system.”

In this society, a little girl caught doing something naughty was seen as a sign of irreparable damage.

“As far as Ann’s physicians were concerned, a little girl caught masturbating was sure to become a danger to men and society — that was, if she didn’t obviate the need for men altogether,” Farley writes.

“ ‘Ann is “man-like” in her urges,’ one physician told her mother, after hearing about her alleged fondness for self-gratification. ‘And if she keeps at her nasty habit, she won’t perceive any need to marry one day.’ ”

In this atmosphere, society declared war on promiscuousness, real or imagined. Politicians established “vice commissions,” with funding from John D. Rockefeller, to “regulate the sexual activity of shop girls, factory workers, and other low-class women,” which even included spying on everyday working women to determine their sexual activity.

“Undercover investigators trailed women from their tenements to their jobs, taking notes on everything from their boots to their professional tasks,” Farley writes. “ ‘There is no question that this woman is on terms of sexual intimacy with her male companions,’ one concluded, having observed a manicurist massaging the hands of businessmen all day.”

This war on women was so intense that the US government imprisoned 15,000 women found to have syphilis between 1914 and 1918.

“Officials claimed to be preventing the women from infecting US troops, who already had high rates of venereal disease,” Farley writes. “Many of the detained women had committed no crime, such as prostitution; they had simply ventured too close to a military base while walking alone or wearing too high a hemline.”

Accordingly, involuntary eugenic sterilization of “poor, disabled, and ‘wayward’ individuals” gained quick acceptance as a way to “reduce the number of unsound people in the population.”

This gave a mother like Maryon, whose only obstacle to her late husband’s fortune was her daughter’s potential reproduction, easy options.

In August 1934, when Ann was 20 and therefore still a minor, she was having lunch with her mother near San Francisco when she felt a rush of pain in her stomach. She was taken to a hospital, where Dr. Tilton Tillman, without ever examining her, told her she had appendicitis.

She received an appendectomy from Dr. Samuel Boyd four days later. During the weeks she spent recovering in the hospital, she heard things that were deeply concerning.

“During this time, she overheard a few staff members ask her nurse how the ‘idiot patient’ was doing,” Farley writes. “Ann also heard her nurse make several phone calls to Dr. Tillman assuring him that his patient ‘didn’t suspect a thing.’ ”

“I learned then that my mother and Dr. Tillman had told everyone that I was a mental case,” Ann later testified. “I discovered that I had undergone a salpingectomy, having my tubes removed along with my appendix.”

Later in her testimony, her attorney asked if she had hoped to marry one day. She replied that she did, then added, “But I don’t know if anyone will have me now.”

Ann filed the civil suit against her mother for $500,000 in January 1936, alleging that Maryon Cooper Hewitt paid the doctors to remove her fallopian tubes without her knowledge or consent. Soon after, the San Francisco district attorney charged Maryon and both doctors with “mayhem,” a rare charge that was “reserved for cases involving the act of disabling or disfiguring an individual . . . punishable by up to 14 years in prison.”

But a lengthy, exhausting trial resulted in the charges being dropped against the doctors and her mother. Ann settled the civil suit for $150,000. Maryon died following a stroke in April 1939 at age 55. Like her mother, Ann wound up marrying five times, before dying of cancer in February 1956 at age 40.

Incredibly, many states that had laws on the books allowing involuntary sterilization did not begin to repeal them until the 1970s.

Farley writes that the Cooper Hewitt family did everything they could to erase the memories of these women from the public imagination, and that only now, with this book, can Ann Cooper Hewitt get the recognition she deserved. “Mortified by the scandalous women and their feud, Peter’s siblings removed papers and records relating to Ann and Maryon from the family’s legacy,” Farley writes. “In trying to remove what they perceived to be a stain on the saga of a great family, the Hewitt siblings helped to erase eugenics from the public memory while upholding the movement’s ideals. The family members may not have bankrolled or publicly supported sterilization campaigns, as many of their peers did, but they shared eugenicists’ disdain for women thought to be disruptive.”

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article