André Leon Talley on the Influential Black Fashion Designers You Should Know

In 2017, The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology presented “Black Fashion Designers,” a groundbreaking exhibition that examines the significant, but often-unrecognized, impact that Black designers have had on fashion. The expansive survey featured approximately 75 looks by more than 60 designers from the past eight decades. These designers included 1950s society dressmaker Ann Lowe, who designed Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s wedding dress; 1970s bright stars Stephen Burrows and Scott Barrie, who defined the disco era’s glamorous body-con style; and rising talents of today, like LaQuan Smith and Pyer Moss designer Kerby Jean-Raymond.

The exhibition was accompanied by a mobile tour with multimedia content for smartphones including archival video footage and designer interviews, which the museum has now made available online. The tour is narrated by legendary fashion journalist André Leon Talley, who recently published The Chiffon Trenches, a memoir charting half a century spent writing and styling for Women’s Wear Daily, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Interview, and more.

Here, we speak with Talley and the exhibition’s co-curator Elizabeth Way about Black designers who have had a large impact on the fashion industry while often being less visible than their peers and, more importantly, how we can change that.

What do you hope for online visitors to take away from viewing the 2017 exhibition “Black Fashion Designers” now?

Elizabeth Way: One of the things my co-curator Ariele Elia and I really wanted to stress with this exhibition is that there is no one definition of Black style. There’s no one style that Black designers design in. We really wanted to highlight the multitude of talented Black designers that have been working in the fashion industry since the 1950s.

There is no one definition of Black style. There’s no one style that Black designers design in.

André Leon Talley: There are many great Black designers. Stephen Burrows is on a par with Halston, who was his contemporary. Mr. Burrows is one of the great, great original talents. He is a self-taught man, and he created the most wonderful color-block clothes in the 1970s, clothes that were full of optimism. They just registered something that had not been seen before in fashion. They were like wearable art.

Scott Barrie was another extraordinary designer of this time. And before Mr. Burrows and Mr. Barrie came on the scene, there was this great woman, Ann Lowe, who went unsung as one of the pioneers of Black style and design.

There’s one of Ann Lowe’s wedding dress in the exhibition—it’s gorgeous!

ALT: Ms. Lowe is historically extraordinary. She was this wonderful lady who had come from the South in the 1950s and created clothes for all the Park Avenue socialites. Society women all up and down the Eastern Seaboard were dressed by Ann Lowe. She designed the gown Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis wore when she wed John F. Kennedy in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, in 1953.

Ann Lowe had obviously seen her grandmother sew, and she created a career out of that. So that is the history of the Black designer, it comes out of the segregated South, it comes out of a folkloric ancestral recall. I would say that ancestral recall is very inherent in the work of the Black designer. Most of them are self-taught, and most of them remember their relatives sewing. This exhibit encompasses many individuals who make up a broader quilt of American fashion history.

I would love to hear more about your memories of meeting these Black fashion stars as a young editor for Women’s Wear Daily in the mid-1970s.

ALT: Well, it was a bit before my time, but Stephen Burrows was included in the Battle of Versailles fashion show in 1973. That was a big accolade for him to be chosen as one of five American designers to face off against the best of French talent. The others were Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, Halston, and Anne Klein. He was the last to show and brought the house down. No one had ever seen so many Black models walking a runway. The soundtrack was Al Green’s “Love and Happiness,” and the clothes had this kind of minimalistic elegance to them. Stephen Burrows’s designs are always attuned to the body. His technique is very much a continuation of what Madame Vionnet created at the beginning of the 20th century. I think that’s important for the history of fashion: He evolved the bias cut.

Scott Barrie’s clothes were very elegant and sensuous, in matte jersey. What I remember most about Scott Barrie is his success as a designer. He lived in a beautiful townhouse on the Lower East Side that was filled with white silk-satin Art Deco furniture. That was unique for me. I went to his house maybe twice. He wasn’t a close friend like Stephen Burrows.

When I left to go to Paris in 1978 to become the fashion editor of Women’s Wear Daily, which was a big moment in my career, Stephen Burrows gave me a going-away party at his house, and everyone important was there: Elsa Peretti; Bobby Breslow, the bag designer; Bethann Hardison. It was just a wonderful moment in time.

Another of your friends featured in the exhibition is the experimentalist Andre Walker. His designs, like a jacket that turns into a capelet/halter top at the back, often hybridize several articles of clothing and they really don’t look like anything else. What can you tell me about his inspirations?

ALT: Andre Walker is another unsung hero of fashion. He’s sort of an underground designer who has been working in fashion since the 1980s. He showed twice in Paris. I went to two shows of his there in the early 1990s. He lives in Brooklyn with his parents who are quite religious. He is self-taught. Andre Walker is an extraordinary human being, and I think that some of the best examples of modern fashion in the exhibit are looks he designed for Rei Kawakubo’s store Dover Street Market.

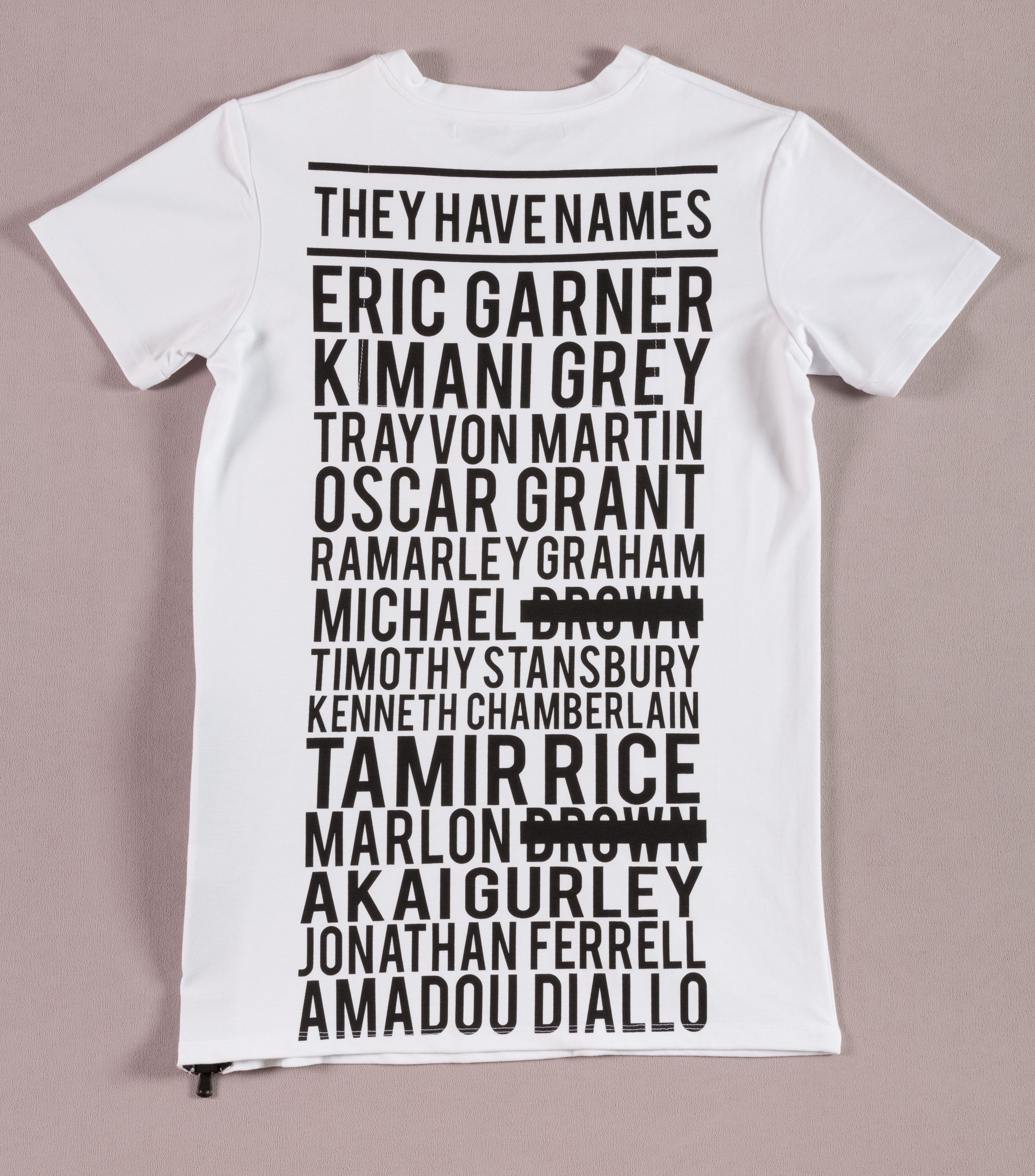

The “Activism” section of the exhibition includes Pyer Moss designer Kerby Jean-Raymond’s “They Have Names” T-shirt from spring 2016, which made a powerful statement in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and feels all the more poignant now. In what ways do you think fashion should use its platform to promote social justice?

ALT: Well, I would say that was one of the most original segments of the exhibit. That was a very powerful moment to use the T-shirts, because T-shirts are a universal uniform. And they are very, very, very relevant today, because there are people in the streets globally protesting for Black Lives Matter. Protesting against the social injustice of the blue murders by policemen of young Black men and women—Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland. They are not wearing high fashion. They are usually in T-shirts. The T-shirt is a very important item of clothing: a man, a woman, a child, a teenager, an elder person can walk in protest in the streets in a T-shirt. It’s comfortable, it’s accessible, and it’s affordable.

A man, a woman, a child, a teenager, an elder person can walk in protest in the streets in a T-shirt.

One of the many things that impressed me about George Floyd’s funeral was that the choir that was onstage behind Rev. Al Sharpton wore black T-shirts that said, “I can’t breathe.” “I can’t breathe” is a very strong, yet sad, important message that we have to really be keeping our minds on the fact that Mr. George Floyd’s humanity was taken out by a man who kept his knee on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds.

EW: That was very brave of Kerby Jean-Raymond, to have that show. He included a video that he made, in which he interviewed the families of victims of police brutality. He lost customers. He lost buyers over that. That was very brave of him to do. I think it’s important and wonderful when designers make statements. But if the fashion industry really wants to make a statement in support of social issues, the change has to also come from the top.

What actions would you like to see the fashion industry take to be more inclusive and supportive of Black designers?

ALT: Global brands including Gucci and Prada have set up initiatives for Black members of the industry to advise them. Gucci was one of the first to have this advisory board that started, I think, about a year ago, which meets regularly to discuss things that are important to the roles of Black talent in the fashion industry. That’s very, very significant.

EW: I agree 100 percent. I would also add that while it’s amazing that people in boardrooms are having these conversations, making this type of educational outreach, change will come when there is more diversity among the corporate leaders themselves.

André, you’ve obviously mentored many young designers. How do you go about that?

ALT: I have to give credit to my former mentors, the editors Diana Vreeland and Carrie Donovan. I had great role models. You just simply nurture through conversation or special opportunities, and encourage them to never give up. For example, I first read about LaQuan Smith in a New York Times piece that described how he was living in his grandmother’s house in Queens and making patterns from newspapers. I remember thinking, This person has got something.

I went to his first show and I was blown away. It was stunning. Stunning in its relevancy and its currency. By the time he had the second or third show, I had Serena Williams walking in it! She was in town for the US Open and I said to her, “You’ve got to come with me and be in LaQuan Smith’s show.” She never had a fitting for the dress she wore, but she closed the show.

LaQuan Smith is so extraordinary that I simply gave him $2,000 of my own money. One day I went and said to him, “Take this check and use it to go to Paris. Paris is the mecca of style and fashion, and just seeing how light falls on the buildings there will inspire you. You don’t have to go to Paris to do a certain thing. I’m not saying you must go to Paris and try to go in and see a designer or get a job.” I said, “Just go there for a couple days. Go sit down and have a cup of hot chocolate, have a croissant, have a café in a restaurant in the open air.” And he did. I saw him recently before the COVID came. I went to the studio in Queens, and he’s still doing great work. He is extraordinary. He is self-made, and it’s extraordinary.

EW: I’d just like to add that the more people we have like you in a position to mentor people, the better. You sent LaQuan Smith to Paris the same way that Pat Cleveland sent Patrick Kelly to Paris. So the more people that we have in high positions, the easier it’s going to be for everyone, because these relationships do happen naturally.

ALT: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

Are there any other new names who have come onto the scene since the exhibition first opened in 2017 that you’re excited about?

ALT: Christopher John Rogers is a great designer. He’s the future. FIT should be trying to get some of his original designs in their collection.

EW: Yes! We’re definitely working on it.

ALT: I also want to say congratulations on your upcoming new boss at Harper’s BAZAAR. It’s a great moment in the history of fashion.

Source: Read Full Article