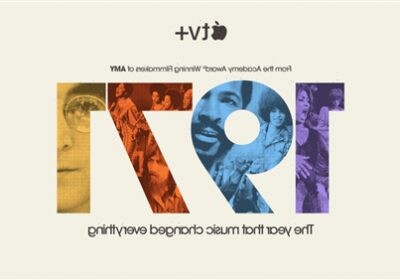

“Just Extraordinary Songs”: Docuseries ‘1971’ Explores Vital Year When “Music Changed Everything”

Fifty years ago at this time, the world was just beginning to absorb the impact of Marvin Gaye’s seminal concept album What’s Going On. The LP, released on May 21, 1971, told a story in music from the point of view of a Vietnam veteran returning to an America beset by poverty, injustice and ecological crisis.

In a plaintive tenor voice, Gaye sang in the title track, “Father, father/We don’t need to escalate/You see, war is not the answer/For only love can conquer hate.”

As revealed in the Emmy-contending documentary series 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything, Gaye’s was not the only remarkable statement made in popular music within that turbulent time frame.

“I mean every major artist—male, female, group, individual—seems almost to a complete level deliver their masterworks that year. So many big records made,” executive producer James Gay-Rees tells Deadline. “Then you sort of ask yourself the question, ‘Well, why? What was going on in the culture and in society that gave birth to so much brilliant music which is still completely iconic today? We just started to ask that question… and threw up some very interesting answers, which are very resonant [to] many aspects of society today.”

Watch on Deadline

It was in “this foul year of Our Lord 1971” (as Hunter S. Thompson put it), that President Nixon first began bugging the White House, and launched his “war on drugs.” In March 1971 a group of left-wing activists broke into an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania and stole FBI files, which contained evidence of the bureau’s domestic spying activities and its scheme to sabotage the Black Panthers. Scholar and Black activist Angela Davis made one of her first court appearances on murder charges, riveting the nation. The series explores those and other events of immense significance.

“It’s talking about an extraordinary psychological experiment called the Stanford Prison Experiment [that took place in 1971], it’s talking about My Lai, it’s talking about Charles Manson,” notes Danielle Peck, one of the directors of the series. “It’s talking about this really kind of tense and difficult year because Lt. [William] Calley was found guilty [in the My Lai massacre] in ’71, Charles Manson was sentenced in ’71.”

Major recording artists were not bystanders to a culture in flux, but central to raising political and social consciousness. As music exec Jimmy Iovine observes in episode 1, “1971, I don’t think the music was a reflection of the times, as much as the music also caused the times.”

George Harrison and Indian musician Ravi Shankar organized the historic benefit Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden in New York. Carole King released her subtly feminist album Tapestry in February 1971; later in the year Sly and the Family Stone came out with There’s a Riot Goin’ On’, an implicit response to Gaye’s album. David Bowie and Elton John took their first bold steps into the world music scene. Joni Mitchell released her masterpiece, Blue.

Incisive political commentary sprang from recording artists like Curtis Mayfield, and poet-musician Gil Scott-Heron. In episode 5 of the series, Brian Jackson, who composed music with Scott-Heron, observes, “We wanted to write about what it meant to be young Black men in America.”

In 1971 Scott-Heron penned “No Knock,” a song about unannounced police raids that included these lines: “…No-knock, the law in particular, was allegedly, um, aheh, legislated for black people rather than, you know, for their destruction.”

It could have been written in 2020 about the death of Breonna Taylor.

About a week after the release of Gaye’s What’s Going On, John Lennon recorded ‘Imagine,’ just one of a number of songs he composed around that time that reflected his increasingly outspoken political views.

“John Lennon would literally sit in bed and read the news and then write a song like ‘Gimme Some Truth.’ They were a direct response to the conservative post-war generation and the issues of the time,” observes James Rogan, another director of the series. “There’s a huge sense of release of inhibition and a sense of freedom that can only be channeled out through this new, relatively still quite young medium of pop music. And that’s why you just get this explosion of songwriting and just extraordinary songs.”

1971’s Gay-Rees and series director/EP Asif Kapadia won Oscars in 2016 for their documentary Amy, about late singer-songwriter Amy Winehouse. Chris King, an EP on 1971, edited both the docuseries and the Winehouse doc. Both projects are noteworthy for being covered from start to finish with archival materials. Present-day interviews shedding light on the themes and events of the series are heard as audio only, with the visuals coming from the era itself.

“We weren’t short on archive,” King says of editing 1971. “I think that’s a good basis on which to start a program like this. It is a very difficult thing to do… With Amy we really only had one small cast of characters—Amy herself and those around her. With 1971 we’ve got a huge, huge cast and so it threw up challenges of who’s speaking and which voice are we going to pick out of the many that we interviewed. The ultimate goal was to make it feel as if you’re in the contemporaneous moment… and then just to bring the voices in to support that. If you cut away in the middle of any of that action from 1971 and see any of those people now, suddenly it’s nostalgia and that’s not what we’re about.”

King adds, “We wanted to be reliving that [time] and seeing it again, seeing it afresh… So much music that we recognize today had its birth in that year. And so we wanted to root it there and make you live that year in a full way.”

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article