These incredibly ornate hair sculptures tackle violence against women, sexism and more

Written by Morgan Fargo

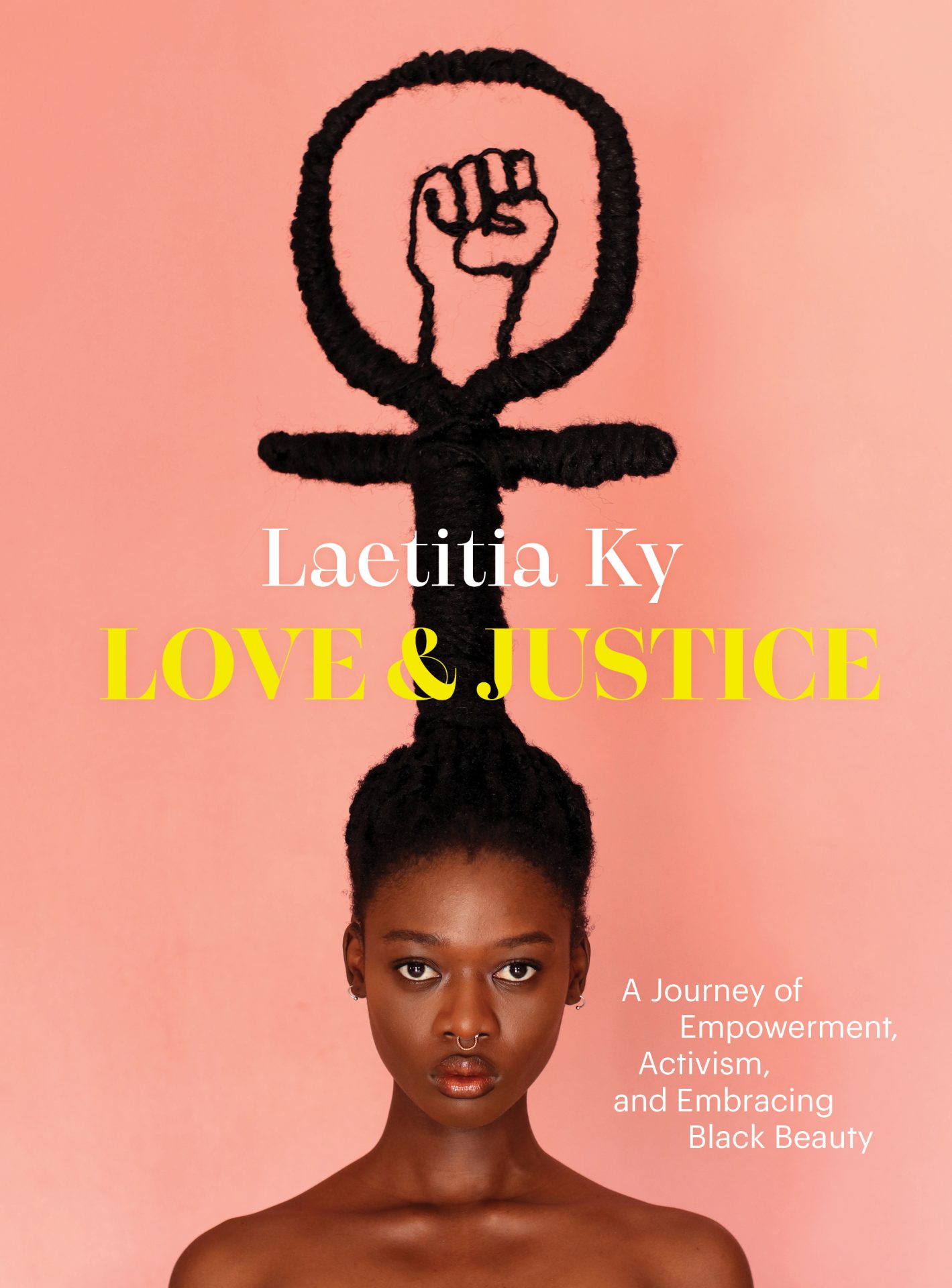

In an exclusive extract from her new book, Love & Justice, Laetitia Ky describes her journey to creating her powerful, poignant hair sculptures.

Author, artist, fashion designer and activist Laetitia Ky is known for her striking – sometimes playful, often poignant – works of art. Using the medium of hair sculptures, Ky uses her own hair, as well as extensions, wire, wool and thread to raise awareness of a myriad of issues women face globally: abortion, female genital mutilation, breast flattening, sexism in the family and violence against women, to name a few.

In her latest book, Love & Justice, Ky shines a light on her journey to accepting and loving her natural hair. In this extract from the chapter Learning to love my roots, she explores her own path to self-acceptance and creating her art.

Reconciling with my African heritage started with my discovery of the African American natural hair community. I was enthralled by all the beautiful Black women on YouTube proudly rocking their natural hair and sharing ways to take care of it. I could have watched these women doing their hair for hours and hours! I had been so conditioned by my environment to relax my hair that it had become as essential as wearing clothes, brushing my teeth, or eating. I couldn’t imagine being happy with a head full of the new growth that was painful to comb if I went a month without relaxer.

Needless to say, discovering the natural hair community was an epiphany. I became deeply introspective about what it meant to have grown up in a world where all of us believed we needed to make a tremendous effort to be enough and to be seen as beautiful. I was so inspired that I decided to shave my head entirely to embrace what the universe had given me. My mom, sisters, and friends didn’t understand my radical shift. My mom thought it was a bad idea because I would lose my relatively long hair without even being sure I would enjoy having natural hair. But she was very supportive and sent me to a hairdresser. It was an emotional moment. As they shaved my head, I cried. What I felt was a mixture of fear and excitement. On the one hand, I was afraid to face who I really was, but I was also exhilarated at the idea of not having to hide my true self anymore.

When it was over, they asked me if I wanted to keep the hair they’d cut. I said no. I was ready to let go of the years of insecurity that my old hair symbolized.

Despite my initial optimism, coming back to my natural hair was extremely hard. The first months were easy because my hair was short. I loved the feeling of my closely cropped 4C coils. My hair wasn’t soft at all, but it was mine. After the fifth month, however, things became challenging as my hair grew longer and required more maintenance. No product was good enough to make my hair soft and easy to comb. The advice on YouTube didn’t help, either: most of the women doing these tutorials had naturally curly hair instead of coils like mine, so the techniques they used didn’t work for me, and the products they were advising newly natural girls like me to use were available in the United States but not in Ivory Coast.

There were moments when my scalp hurt so much from combing my hair that I cried. Sometimes, I even experienced a sense of vague regret for my decision to go natural—a feeling I quickly turned away. Today, I’m so happy I didn’t go back to relaxing my hair, even when my decision felt hard. Of course, I made so many mistakes with my natural hair in the beginning that I had to do another big chop after a year. Braids, weaves, and wigs helped me a lot during that phase—this time, I wasn’t using those styles to hide my hair but to protect it. Wearing protective styles helped me to avoid unnecessarily stressing my hair, as Type 4C hair, the most densely packed and tightly coiled, tends to be more delicate than other hair types and doesn’t require daily combing and manipulation.

I continued to learn about my hair, and over time, it felt better. In 2016, my favorite protective style became Havana twists—twists made with kinky hair extensions that look like real 4C hair. In addition to being pretty, they are easy to moisturize and wash. Also, when I used regular braid extensions, you could easily see the difference in texture between my hair and the extensions after just a week. With kinky extensions, I didn’t have that problem.

The more time that passed, the more I chose protective styles that look like natural hair, because I was starting to appreciate everything associated with being Black. Instead of choosing straight, wavy, or curly hair extensions, I selected the coiliest Afro textures I could find. I had once rejected my natural hair, but I now gravitated toward kinkiness and all its textured glory.

Learning to love my hair naturally helped me to love and appreciate my other Black features, including my beautiful dark skin and my face with its big nose. Falling in love with my hair made me fall in love with my Blackness. I began to appreciate the African aesthetic, with its vibrant hairstyles, clothes, and colors. In this period, I pierced my septum—a trend that is currently popular but is inspired by the traditional style of Fulani women, an ethnic group in West Africa. My preferred clothing and jewelry had a distinctly African flair, and these new styles became a way of expressing my pride in my origins and my inner self.

Looking for inspiration, I started to follow a lot of Afrocentric pages on Facebook and Instagram. One day, while scrolling through social media, I came across a photo album of traditional hairstyles worn by African women in the early twentieth century. The hairstyles were impressive, beautiful, and uniquely Black. They made me want to experiment with my own kinky braids, which I was now wearing every day.

This is how I started the art of sculpting with my hair. For my first sculpture, I attempted to make my hair stand high. When I saw it was possible, I instantly took a photo and posted it on Facebook — all my friends were amazed. The reactions were so positive that I started posting more and more photos of new and exciting styles that revealed the range of possibilities. Each photo I posted got more likes, comments, and shares than the previous one.

The encouragement kept me going.

Buy now

I am touched by all the comments from Black women who have informed me that they used to hate their hair, but that seeing my work has instilled in them a new appreciation for their features. Once, a woman told me she convinced her five-year-old daughter not to ask for straight hair after she showed the child my photos. This touched my heart. Another Ivorian woman also told me she stopped using skin-bleaching products because I was the first person to show her how beautiful dark skin can be. Many artists have said that I’ve given them the motivation to express themselves wholeheartedly, even when they are unsure of how others will respond or even if people will like their art.

I’ve learned that by choosing not to relax my hair, I am reclaiming my heritage—and that in unabashedly being myself, I’m giving others space to be true to themselves and to recognize and celebrate their own unique beauty.

Taken from Love & Justice by Laetitia Ky (Princeton Architectural Press, £19.99) – out now.

Main image: Laetitia Ky

Source: Read Full Article