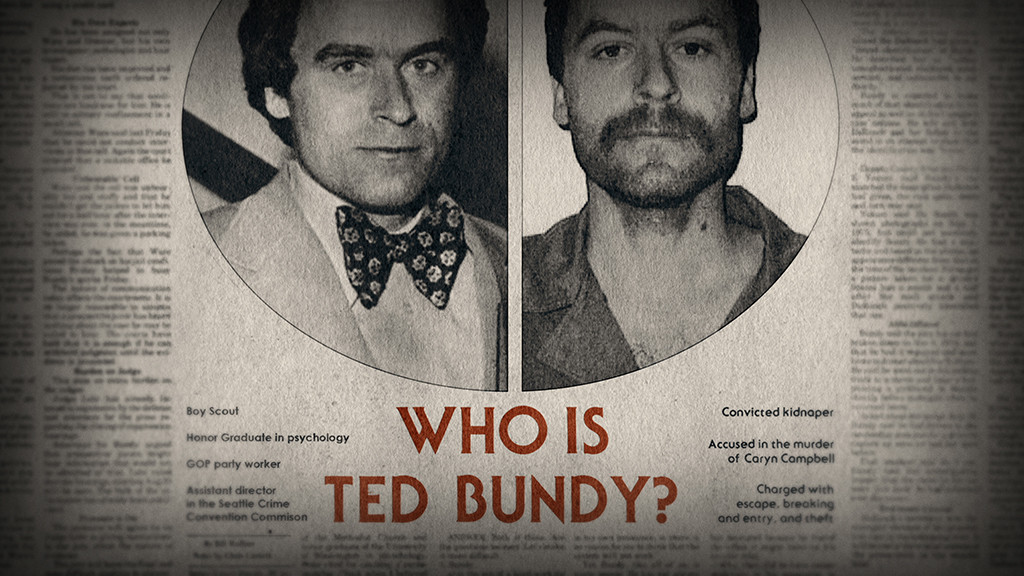

Inside the Horrific Legacy of Serial Killer Ted Bundy

Netflix

Looking at photos of Ted Bundy now, it’s hard to see what unsuspecting people saw in the 1970s.

Which, according to so many, was a handsome, charming man.

That’s been the forever-buzz on Bundy, the serial killer who was executed 30 years ago today and is the subject of both a new Netflix docuseries and an upcoming film starring the unarguably good-looking Zac Efronthat he was a guy who had no problem getting women to let their guard down around him due to his numerous socially acceptable traits.

“Bundy represents for us our most primal, deepest, darkest fear, which is that you don’t know the person next to you,” Joe Berlinger, director of the Efron film, the aptly titled Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, and executive producer of Netflix’s Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, tells E! News.

“We want to think that serial killers are easily identifiable, that once you see them you know, ‘OK, that guy must be a serial killer,'” Berlinger continued. But “people really liked him.”

Bettmann/Getty Images

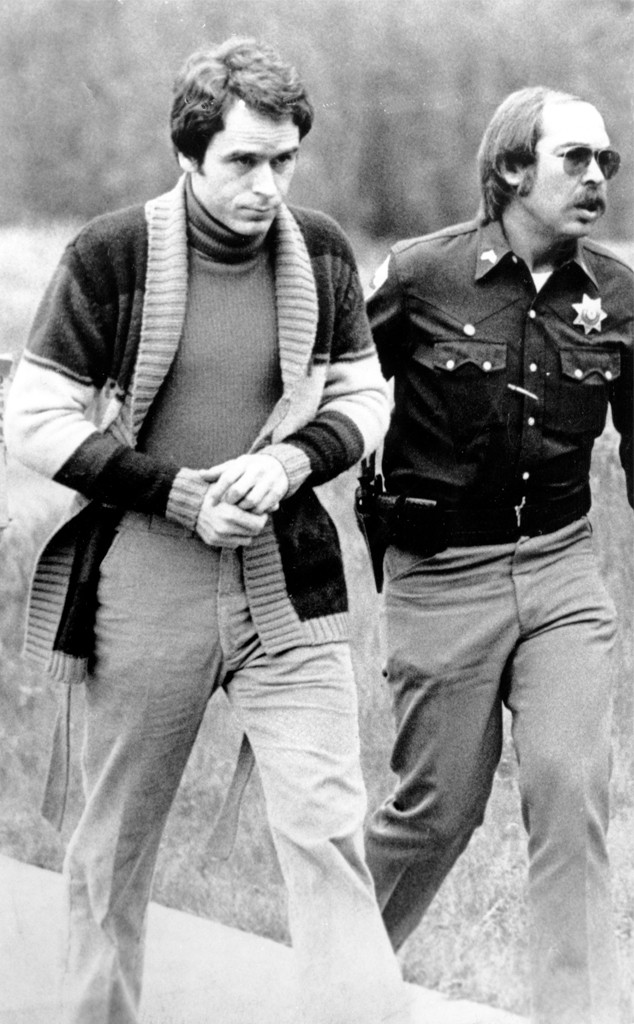

And they liked him until the day he died at 42 years of age in the electric chair at Raiford Prison after confessing to the murders of 30 women.

“I shouldn’t be surprised that I still get letters and emails from twenty-year-olds who are fascinated with Ted Bundy,” wrote Ann Rule in a 2009 update to her 1980 best-seller The Stranger Beside Me (which was made into a 2002 TV movie starring Billy Campbell as Bundy). “Thirty years ago, I watched the Florida girls who lined up outside the courtroom in Miami, anxious to get a place on the gallery bench behind his defense table.

“They gasped and sighed with delight when Ted turned to look at them.”

Rule, who died in 2015, befriended Bundy after meeting him at, of all places, a suicide hotline office in Seattle where they were both answering phones on the night shift.

Lorimar Prods/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

The true crime renaissance has of course taken on a shade of the glamorous thanks to trending podcasts, probing documentaries and deep-pocketed, savvily written limited series that have been dominating the major award shows. But the glamour almost never stops and starts with the killer himself. Bundy proved the exception to that rule almost from the beginning, with first the very appealing Mark Harmon playing him in the chilling 1986 TV movie The Deliberate Stranger, and now Efron.

“It doesn’t really glorify Ted Bundy,” Efron told Entertainment Tonight last March. “He wasn’t a person to be glorified. It simply tells a story and sort of how the world was able to be charmed over by this guy who was notoriously evil and the vexing position that so many people were put in, the world was put in. It was fun to go and experiment in that realm of reality.”

And it is exponentially more chilling when the devil comes calling looking like the college boy next store.

AP Photo/Robert Kaiser

“Ted was never as handsome, brilliant, or charismatic as crime folklore has deemed him,” Rule wrote. “But, as I have said before, infamy became him…I always believed that time would blur the interest in Bundy, particularly after his execution. Instead, he has become almost mythical.”

Bundy wasn’t a mastermind. Countless women refused his ruse, which usually included an entreaty to accompany him to his car for some reason, meaning he left witnesses behind practically everywhere he went and circumstantial evidence abounded in his car and apartment. Yet at the same time, he was both unassuming and handsome enough not to trigger alarm bells for lord knows how many people, some of whom didn’t know how lucky they were to live to tell the tale of the cute fellow who approached them at the park, or beach or bus stop.

He blended in, and even though dozens of people saw his ultimately infamous tan Volkswagen Beetle, that didn’t stop him from driving it across state lines, back and forth. And he was brazen, sometimes driving for hours with dead girls in his car, and returning multiple times to where he dumped their bodies to visit their remains.

Netflix

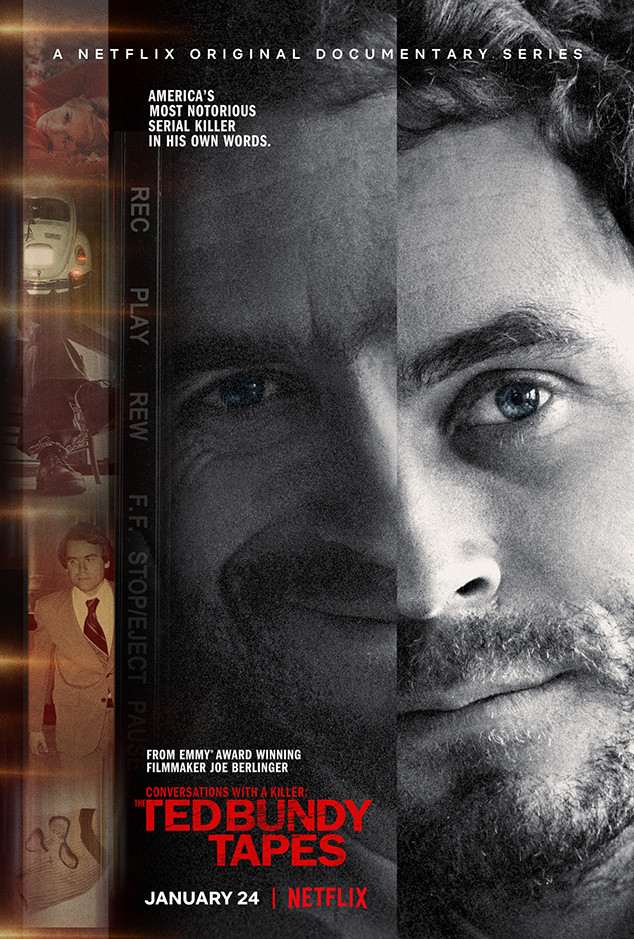

Berlinger explains that, aside from it being the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s execution, the impetus for the Netflix series was their acquisition of taped interviews that journalists Stephen G. Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth conducted with the murderer on death row in 1980.

“It’s entering into the mind of a killer,” Berlinger says, “to understand how somebody could be so deceptive, so manipulative, and what makes him tick. I think it’ll be utterly fascinating for people.”

In their 1983 book The Only Living Witness, since updated, Aynesworth and Michaud call Bundy “handsome, arrogant and articulate.” Women of all ages, not just misguided twentysomethings, flocked to get a glimpse of him when he went on trial in Miami for murdering two Florida State sorority sisters and attacking two others, as well as another student in an apartment eight blocks away, in a bloody spree on Jan. 15, 1978. All three survivors testified at trial.

Acey Harper/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

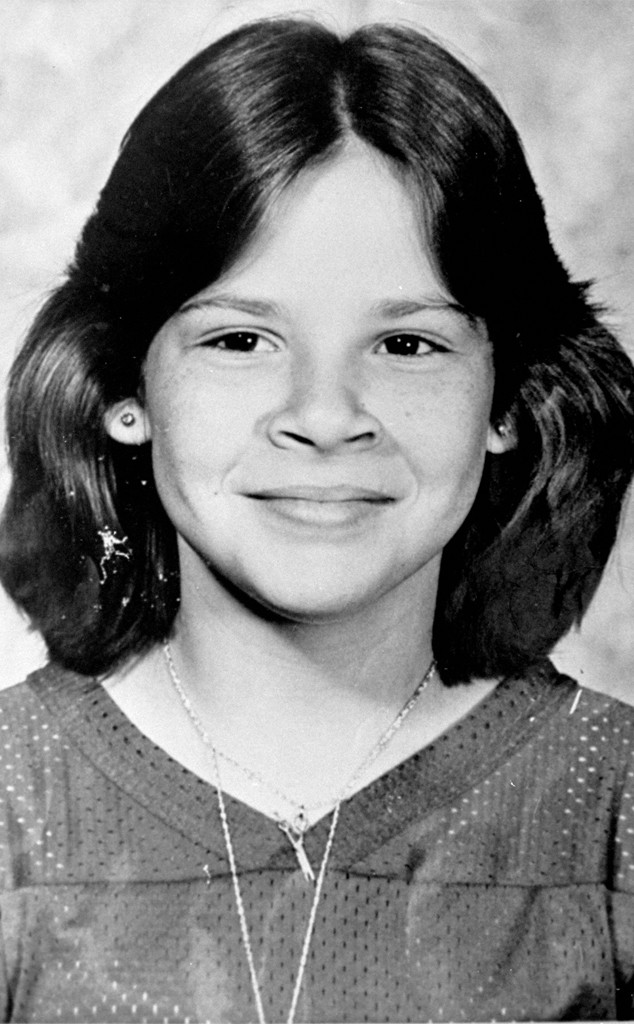

Then went on trial again in Orlando for the Feb. 9, 1978, kidnapping and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach.

He was convicted and sentenced to death for all three murders, though technically the crime he was executed for was killing Leach, a junior high student who disappeared from school on her way to her homeroom class to retrieve her purse. Her remains were found seven weeks later in a hog shed by Suwannee River State Park.

Ultimately, however, these three murders were the sloppy climax of Bundy’s epic display of savagery wrought over four years in seven states. Before he was executed he confessed to 30 killings, which doesn’t mean he wasn’t responsible for more, and over the years he played along with the not-farfetched assumption that he may have been responsible for at least 100 murders, not including numerous attacks.

“I don’t think even he knew…how many he killed, or why he killed them,” said the Rev. Fred Lawrence, who administered Bundy’s last rites, according to David Von Drehle’s 1995 book Among the Lowest of the Dead: The Culture of Death Row.

The nature vs. nurture debate is one for the ages, but the man born Theodore Robert Cowell is ripe for discussion.

His mother, Eleanor Louise Cowell of Philadelphia, gave birth to him at a home for unwed mothers on Nov. 24, 1946, sent there by her deeply religious parents, who at first set about raising him as their own so as to spare themselves the shame of having an illegitimate grandson.

AP Photo/Mark Levy

His birth certificate lists a salesman named Lloyd Marshall as his father, though his mother later mentioned being seduced by “a sailor.” Yet another theory is that his maternal grandfather—a violent, abusive man—was his biological father.

Cowell moved 4-year-old Ted to Washington in 1950 and married Johnnie Bundy two years later, but though Ted had his adoptive father’s name, he didn’t have a close relationship with him or his step-sisters and resented being moved away from who he thought was his dad (and maybe was his dad). When Bundy ultimately found out about his parentage, he resented being lied to, regardless.

Before he turned 18, Bundy was arrested twice for burglary and car theft, but nothing violent. However, when he was 14, an 8-year-old girl who took piano lessons from his uncle disappeared. Down the road, Bundy actually denied having anything to do with that and there’s no proof that he did, but Ann Rule, among others, believes the child was Bundy victim No. 1.

The shy teen enrolled at University of Puget Sound, then transferred to University of Washington, where he started dating classmate Stephanie Brooks (a much-used pseudonym). Bundy dropped out of college in 1968 and Brooks broke up with him shortly afterward, citing his lack of seriousness and ambition, and he ended up leaving town, eventually ending up at Temple University for one semester.

Once back in Washington, he met Elizabeth Kloepfer, a divorced secretary at the UW School of Medicine, and they dated off and on for years. Bundy re-enrolled at UW in 1970, met Rule as a volunteer at Seattle’s Suicide Hotline Crisis Center in 1971 and graduated in 1972. Bundy, who had attended the Republican National Convention in 1968 as a delegate for Nelson Rockefeller, went to work for Gov. Daniel Evans’ successful reelection campaign. That opened a few more doors in the political world, and then he was admitted to law school at Puget Sound.

According to Rule, he rekindled his relationship with Brooks during a trip to California in the summer of 1973, then broke off contact with no explanation. When she reached him by phone to ask what happened in early 1974, he calmly said, “Stephanie, I have no idea what you mean,” and hung up.

Source: Read Full Article