A New Memoir Demonstrates Just How Much Work It Takes To Be Poor In America

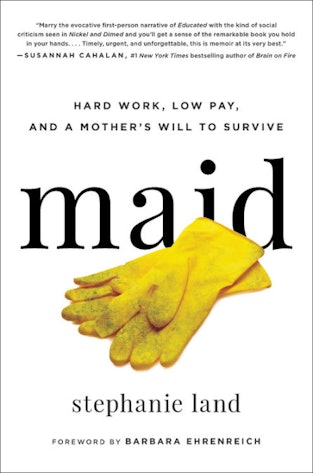

Growing up, when Stephanie Land thought about her future, poverty was the furthest possibility. “Inconceivable, so far away from my reality” she writes, in her debut memoir, Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and A Mother’s Will To Survive. “I never thought I would end up here.” Then, one child and one breakup later, the then-28-year-old Land found herself in a homeless shelter, watching her one-year-old daughter learn to walk.

Her daughter’s father had depleted Land’s savings, then left her with nowhere to live. So with no job, no college degree, and a newly mobile one-year-old at her side, Land did what single mothers everywhere are forced to do: she found a way to survive. She took a minimum wage job as a house cleaner, and when that wasn’t enough to pay the bills, she turned to government aid. As a result, Land found herself straddling two worlds: one of large, sprawling homes with countless surfaces to clean, and that of a single mother living in poverty.

Maid is the story of Land’s journey through those two worlds, and of the sheer force of will it took to keep her and her daughter afloat. In one sense, it’s a story of poverty to possibility. But it’s also a story of the nearly superhuman demands society places on mothers, on single mothers in particular, and most especially on single mothers living in poverty.

‘Maid’ by Stephanie Land

$16.20

Amazon

For Land, it wasn’t difficult to end up in poverty. In fact, all it took was two critical and not a-typical life events: the birth of her first child and a breakup. But once Land, a then-minimum wage worker, entered the world of government aid — Medicaid, low-income housing, food stamps — it was nearly impossible for her to get out of.

“It’s a lot of work and a lot of scrambling around — not only to prove that you’re working, but to prove that you don’t have any money,” Land tells Bustle earlier this month. “You’re not allowed to save money, you’re not allowed to have a nice car, in some states you can’t have more than $1000 in your savings account. And you’re discouraged from improving yourself, because if you get a $100 more a month from a promotion you could lose $400 in benefits, so there’s this huge financial gap that you have to jump over in order to get off [of public aid].”

As Land describes in her memoir, trying to make ends meet on a minimum wage income requires a staggering amount of work. Navigating the world of public aid almost becomes another part-time job: There are countless applications to fill out, requirements to meet, documents to organize, caseworker meetings to attend, paperwork to submit, and frequent, inconveniently-timed re-certifications for everything from free school lunch for your children to healthcare for your family. All of which, for a single mother like Land, has to be accomplished on little sleep, poor diet, and inadequate healthcare, while managing the round-the-clock task of childcare. If there’s one thing Land wants her memoir to get across to readers, it’s this: Poverty is hard work.

“That’s what I’m hoping to get across — how much work it takes to be poor,” Land says. “If you’re a single mom, you do all of the domestic work by yourself, all of the work that’s required to qualify for government assistance, and you have all the extra, daily burdens that come with being a poor person: you’re constantly scrambling. The stress that’s involved makes life really different.”

She’s also hoping that Maid helps to combat the stigmas that people living in poverty often face. She writes of the responses she’d receive when using food stamps in the grocery store — the looks of impatience and judgement she’d observe in her fellow shoppers, the time a man shouted “You’re welcome!” as she left a checkout line, as though his tax dollars had personally paid for her dinner.

“[People on welfare] work,” says Land. “They work very hard. I can’t say that enough. Poor people work really hard.”

Those stigmas and stereotypes — that people on government assistance don’t work, or don’t want to work, or aren’t working hard enough, were difficult for Land to grapple with — not just from others, but even from herself. In Maid, she writes about how she could never work enough. If she wasn’t at her job or taking care of her daughter, she still felt like she had to be doing something. She felt that taking time to read a book, or to even sit down, immediately made her the “lazy welfare recipient” that society already expected her to be. “Our society tells you that if you work hard enough, ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’, that you’ll make it in America. That’s where all the stigmas begin, I think,” she says. “People assume that if they’re not making it they’re not working hard enough — and that was really hard for me.”

Ultimately, Land was able to enroll in school. She earned her Bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Montana in 2014, and made a living as a full-time freelance writer. The stories Land tells focus on social and economic justice. The personal essay that inspired Maid — ironically, the same essay that was rejected by the MFA program Land applied to — went viral on Vox in 2015.

“I feel very strongly that the only way anything is going to change is if we start listening to the people who are living the lives we want to change,” Land says. “I think there’s so much power in a first person narrative, from a person living on the margins. It seems that people are listening — or they’re ready to. The worse things get, the closer to home [poverty] becomes — people are paying attention.”

Source: Read Full Article